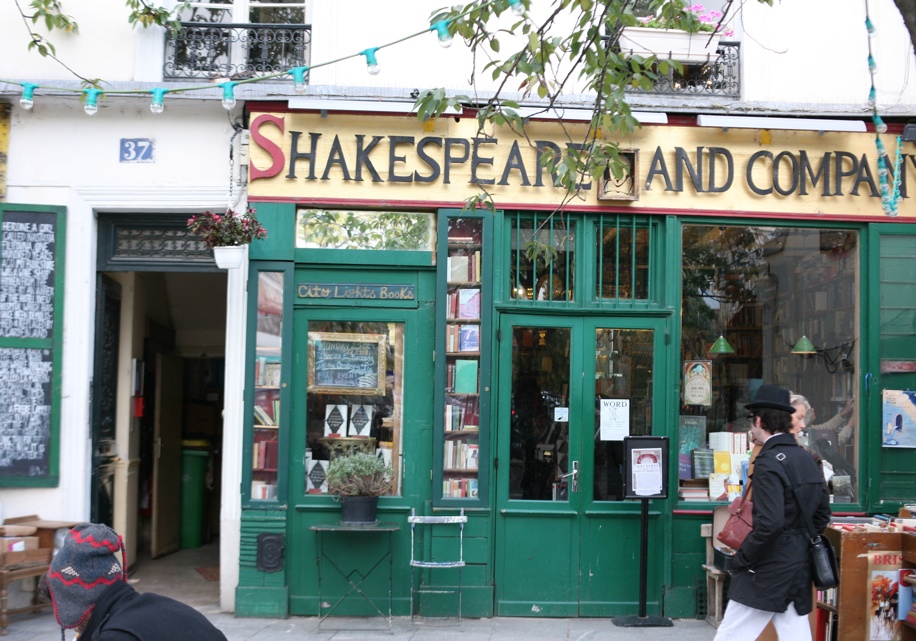

Shakespeare and Company. 37 rue de la Bucherie, 75005, Paris

Let me tell you a story. A perfectly circular one, shaped by fate. There once was an American woman called Sylvia Beach. She was studying literature in Paris when she fell in love with Adrienne, a French bookshop owner. Sylvia set up her own English language bookshop, across the road from Adrienne’s, on the Left Bank. She named it Shakespeare and Company. Sylvia’s enthusiasm for books and authors meant that her shop became home base for writers and poets passing through Paris. Some were rather famous, with names like Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Eliot, Pound, Gide, Stein, Beckett and Lawrence. Many became her friends and protégés; she championed, fed and housed those whom she could. For a writer called James Joyce, Sylvia really outdid herself. She published the first edition of Ulysses, at her own great expense, when no one else would.

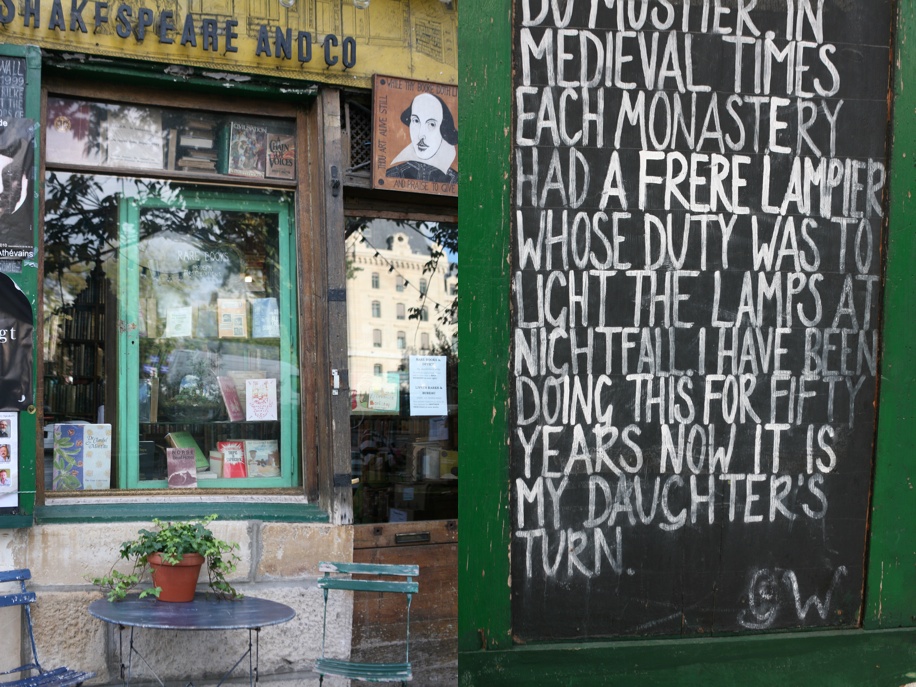

Sylvia’s Shakespeare and Company was forced to close during the occupation of Paris. It never reopened, despite being “liberated” by Hemingway, who drove his tank right up to the shop to tell his friend about the end of the war. Sylvia died in 1962, but not before passing the torch to a new American bibliophile in Paris: George Whitman. An ex-serviceman and an impassioned traveler, George studied at the Sorbonne and was living in a hotel in the heart of the Left Bank. He collected books. George’s room had no lock and was overflowing with volumes, loaned freely and often to whoever passed through his door. His longtime friend, poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti (now the owner of City Lights in San Francisco) convinced him to open a shop. After one failed attempt – a floating barge of wet books – George used his small inheritance to purchase a boarded up old flat on the bank of the Seine, opposite the Notre Dame Cathedral.

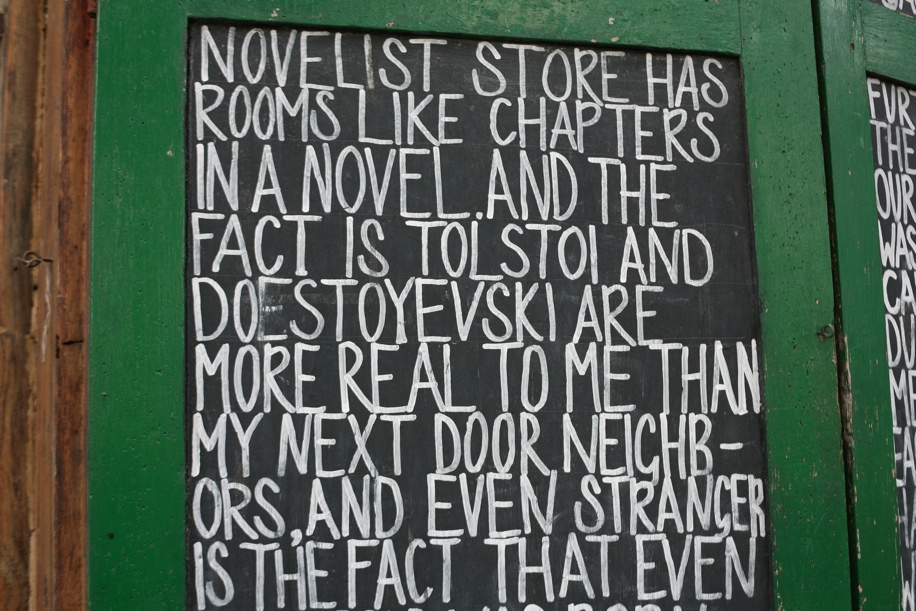

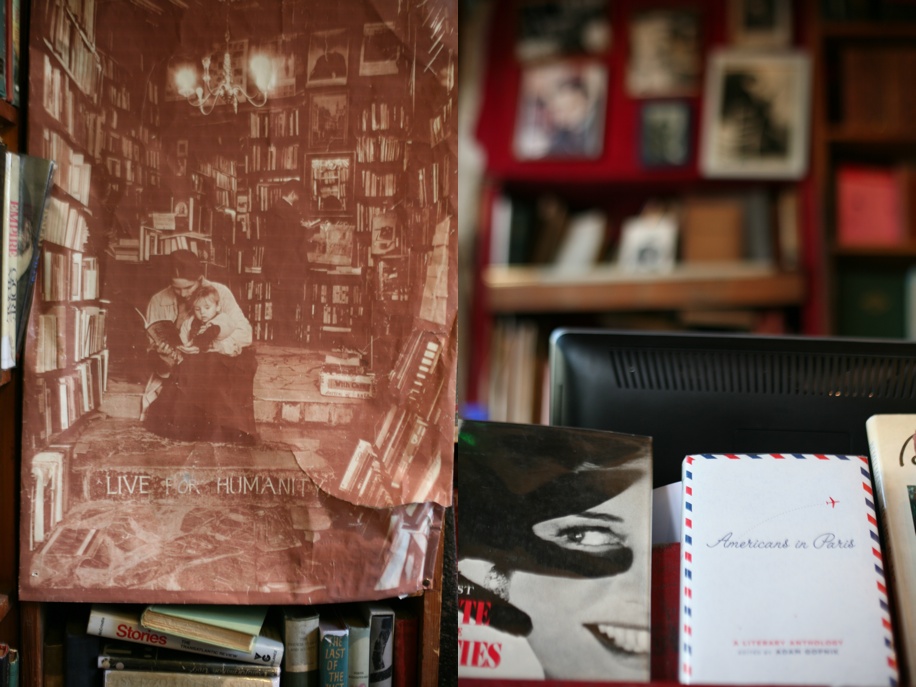

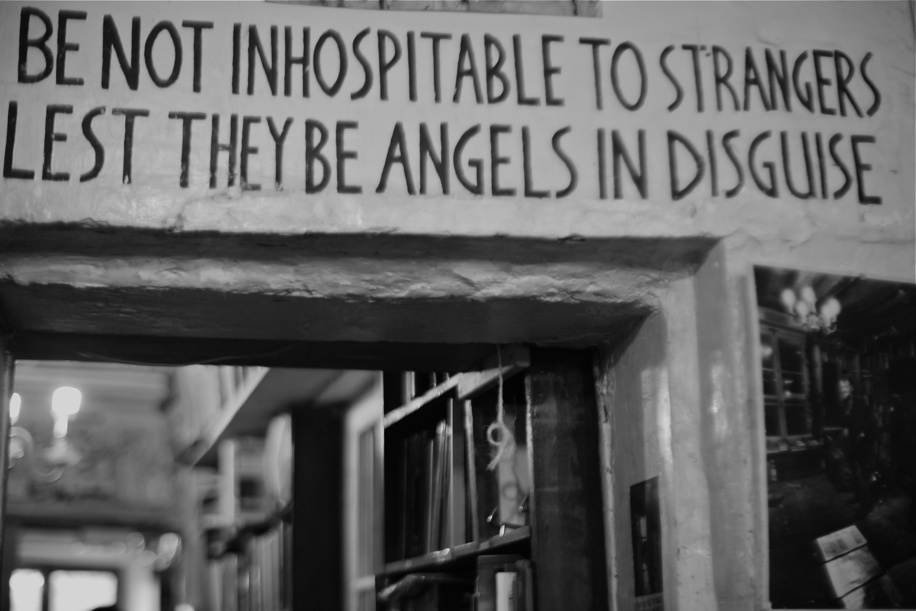

From the very beginning, George’s place, like Sylvia’s, was much more than a shop selling books. “The Mistral,” as it was originally known, was a writers’ sanctuary in Paris. At first, they slept on mattresses strewn around the nooks and crannies of the shop’s first floor, but gradually, as George acquired more and more rooms in the building, his bookshop became… a utopian kind of hotel; a commune; a place to sleep, be inspired, read, write and work. George is generous to the core; he remembers well the kindnesses shown to him in his past. His life philosophies are plastered around the shop like mantras: “Live for humanity.” “Be not inhospitable to strangers lest they be angels in disguise” and “give what you can, take what you need.” George referred to his drifting tenants as “tumbleweeds.” To earn their keep, they were charged with writing a one-page biography, reading a book a day and helping out in the shop. Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Lawrence Durrell, William Burroughs, Henry Miller, Anais Nin and tens of thousands of other writers: all shared George’s space, whether staying for a week (or in one case, seven years), performing readings in the ‘library,’ or simply joining George in his upstairs apartment for Sunday pancake breakfast, cooked in an ancient frying pan. George later changed the name above his door to Shakespeare and Company.

Then another Sylvia came along. Sylvia Beech Whitman, named in tribute to the first, was born in 1981. George’s daughter grew up amongst all those stories, spoken and read. She played in the windows overlooking the Seine. She was the audience for the enchanted theatre of the bookshop’s everyday. Sylvia left to board at a Scottish school and an English University before she decided it was time to return to her father. He was 88 or 89, still running and living in the shop, and she hardly knew him. I ask how this could possibly be, having seen photos of an adoring papa with his beautiful blonde daughter. “His life, his world is the bookshop. And if you’re not in the bookshop, it is almost like you do not exist.” But Sylvia now understands. In Paris, aged 21, she quite unexpectedly fell in love: with books, with reading, and with her father’s shop. So much so, that she never left. When George retired, at the remarkable age of 92, she became its new proprietor: “it didn’t feel like a choice.”

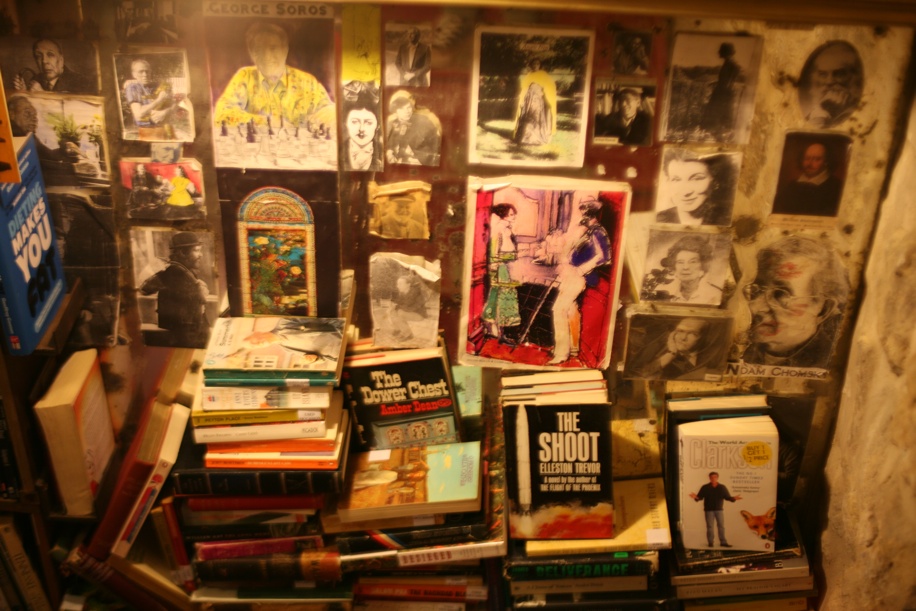

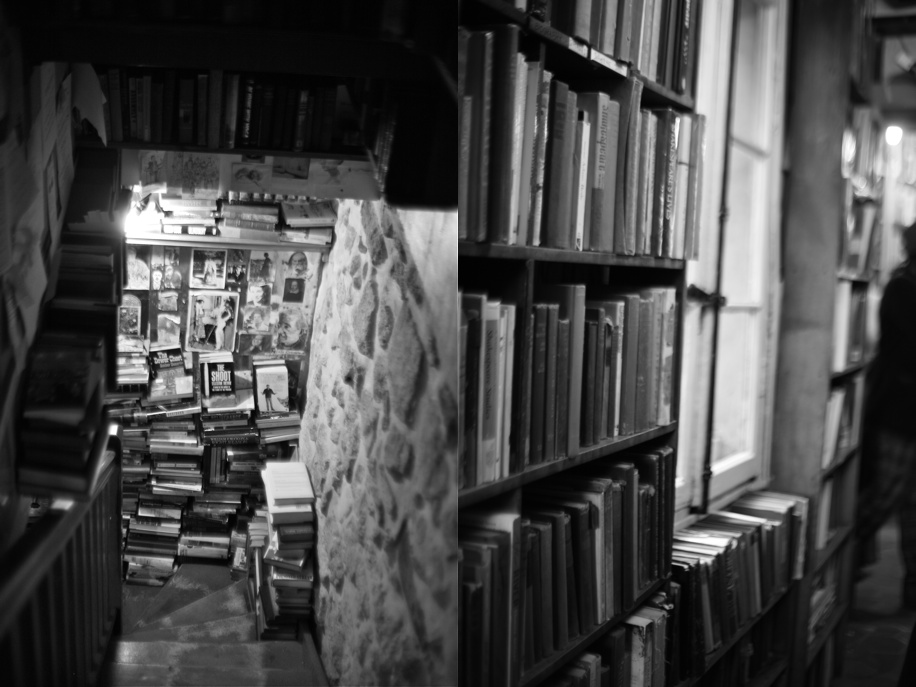

Sylvia Beech once wrote that “a bookshop is mostly tiresome details all day long and you have to have a passion for it. . . I have always loved books and their authors, and for the sake of them swallowed the rest of it, but you can’t expect everyone to do the same.” Two generations on, her namesake has risen to the challenge. In making Shakespeare & Company her own, Sylvia Whitman has managed to transform the shop without changing very much. She has made sense of the place without disturbing its essence. George’s approach as a bookseller was gloriously bohemian; no rhyme or reason ruled the roost. His focus wasn’t profit. “Books, people, ideas. That’s what matters,” said he. As Sylvia puts it, the shop “made sense to him, but no one else, really.” Walking into the shop, one faced walls and walls of towering books, piled haphazardly from floor to ceiling, in every conceivable inch of the space. Legend has it that someone once found tens of thousands of francs in the pages of a book pulled off the shelf. George said he’d misplaced it.

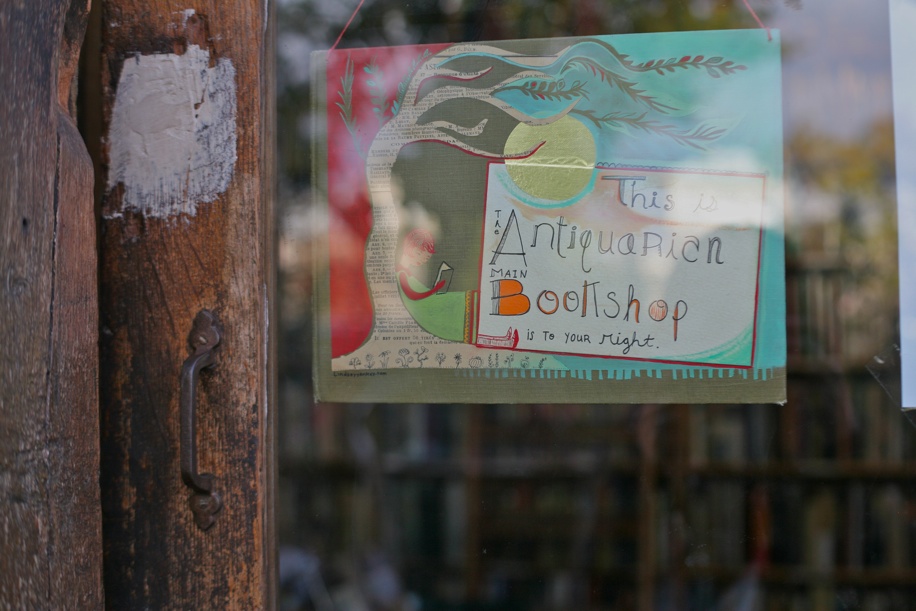

Books still fill the rooms of Shakespeare & Company, and the visual effect is still charmingly chaotic, but now they’re alphabetized so you can find what you’re looking for. Rare and first edition books are safely housed in the ‘antiquarian’ room next to the main shop, while George’s personal collection – featuring books once owned by Graham Greene, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre and Sylvia Beech, among others – is in the upstairs library. The library is a special room with a haunted depth to its air. Lined with old wooden benches, a row of comfy chairs and an old writing desk facing the Seine, this tiny space continues to host authors, musicians and thespians for weekly readings and events. But Sylvia has breathed new life and space into the shop by introducing a biennial summertime literary festival in a nearby square. Last summer, “FestivalandCo” attracted 6000 people. Participants included Martin Amis, Hanif Kureishi, David Hare, Philip Pullman, Will Self, and Jeanette Winterson.

Sylvia says the best thing about running Shakespeare & Company is taking home a good book every day. Then she concedes that it’s the people in the shop who are truly the best part, because they give life to the books. The “tumbleweed” tradition ensures the shop’s community is an ever-changing cast of writers and book lovers from all over the world. That may sound like an intimidating crowd, but the transitory, ‘jump on jump off’ nature of the place makes it friendly, broad-minded and unpretentious. As Sylvia says: “It’s just a lot of pure book lovers of all ages. There’s really no sense of ‘Oh you must have read every single thing in here,’ it’s just ‘Oh this is such a good story, I’m going to pass it on to you.” As I take photos, I overhear a woman with a thick and indefinable accent ask a young American guy to help her find what he thinks might be stories by Roald Dahl. After three unsuccessful guesses, they are both laughing. She leaves, happy with something else. Someone in the corner is talking about trying out a Kindle. Everyone has a story and wants to hear your own. It makes for a fascinating atmosphere. And an intense one. As I talk to Sylvia, who is beautiful, astute and sort of whimsical all at once, three different tumbleweeds come in and address her like she’s their best friend. She respects the fact that what she’s running is a family business – so people expect a personal touch. She finds space and time for herself when she steps off the ‘island’ and explores her own Paris. George still lives above the shop, but his daughter chose to live nearby, instead.

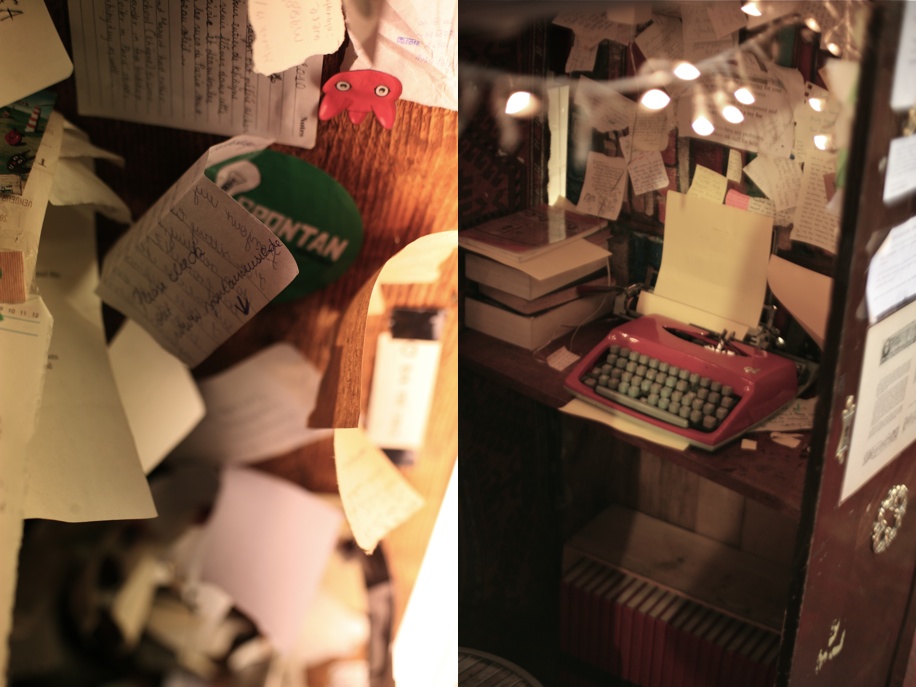

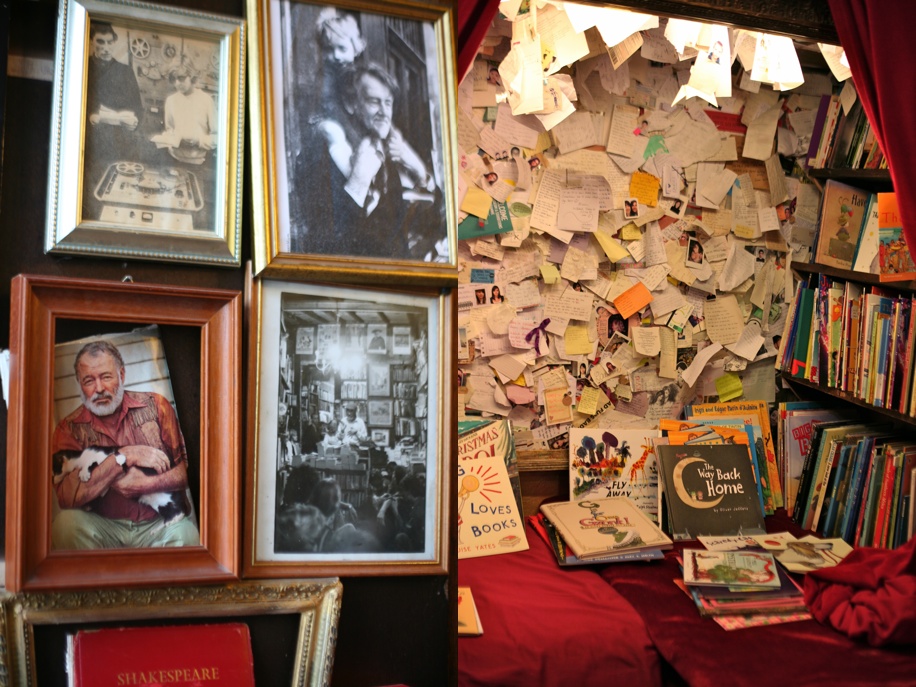

There is a strong sense of communal ownership at Shakespeare and Company. The bookshop exerts its own personality, and yet everyone has left a mark. Upstairs there is a small booth containing a typewriter and chair, its walls lit with fairy lights and littered with notes left by visitors. A comfy corner crammed with children’s books is similarly customised. People from all over the world have left greetings, impressions, signatures, doodles, photos and fragments of their own poems and stories; a physical record of inspiration. There is, too, an archive of the shop’s writers-in-residence. Sylvia and George have kept books full of the tumbleweeds one-page biographies – stories of the lives of those who called the shop home. Photographs of these writers, George and of both Sylvias grace the walls like family portraits, and the main stairwell immortalizes some of the shop’s most notable literary heroes; my friend Badaude, a sort of artist-in-occasional-residence, has captured them in her inimitable illustrative style.

Sylvia Beech’s goal of nurturing English language writing from within the heart of Europe has become the bookshop’s lasting heritage; Shakespeare and Company remains a bastion of literature in English without precluding its French location, customers or writers. From George, the bookshop inherited its ethic, its heart and soul. He has said that the shop is “his unfinished novel” where “every corner is a chapter” in his book. I ask Sylvia Whitman where this leaves her. “The footnote…?” she laughs. I think not. I’m betting Sylvia will still be adding chapters when she is 92. She would seem, at the moment, to agree. “This family business idea used to be the norm, but now it seems strange. Out of all my friends I seem to be the only one who is in a family business, who seems to know what I’ll be doing in 50 years time. . .and very happy about it.” The story of Shakespeare and Company has come full circle. And it ends with a ‘happily ever after.’